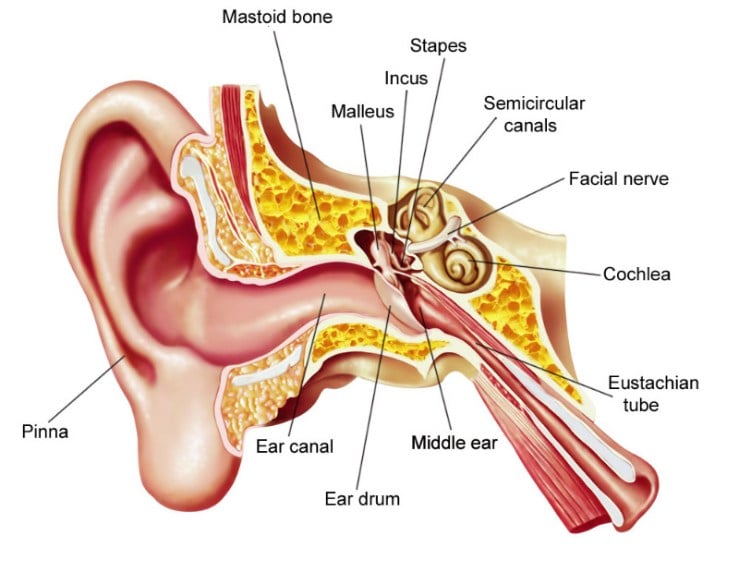

CholesteatomaPLEASE NOTE - THIS INFORMATION IS INTENDED FOR GUIDANCE ONLY. IT IS NOT IN ANY WAY A SUBSTITUTE FOR A SPECIALIST CONSULTATION. What is cholesteatoma? Cholesteatoma is essentially ingrowing skin in the ear. Despite what its name may suggest, it is not a tumour, and it is not related to cholesterol. The ear drum and ear canal are lined by skin. This skin normally cleans itself by moving very slowly outwards, starting at the middle of the ear drum. The top layer of dead skin is only shed when the skin reaches the outside part of the ear canal - this is how we produce ear wax. If there is a hole at the edge of the ear drum, or if the ear drum has become very collapsed, this skin can start to grow inwards instead of outwards. There is a bone above and behind the ear called the mastoid bone, and the cholesteatoma can start to grow into this. What are the symptoms of a cholesteatoma? Most patients with cholesteatoma will have problems with repeated ear infections. The infections aren't usually painful but produce a discharge from the ear, which can smell unpleasant. Some patients may just notice a hearing problem. Occasionally patients are not aware they have a problem with the ear until a doctor examines their ear for another reason and discovers the cholesteatoma. What happens if cholesteatoma is not treated? Although it is not a tumour, cholesteatoma can cause significant problems if it is not treated. It often sets up an infection in the mastoid bone and can also start to eat away at the bone. The first structures that are affected are usually the bones of hearing (ossicles). Often these have been partly destroyed before the cholesteatoma is diagnosed. This tends to cause a partial loss of hearing. Because there are several important structures in and close to the mastoid bone, the cholesteatoma can cause some serious complications. It is important to realise, however, that these serious complications are fortunately quite rare, and if they do occur tend to do so only in patients who have had cholesteatoma for a number of years. The cholesteatoma can erode into the inner ear structures of hearing and balance. This may cause severe dizziness or a complete loss of hearing and balance function in that ear. The nerve that controls the muscles of the face runs through the mastoid bone. If the cholesteatoma affects this it can cause weakness or paralysis of one side of the face. This may be permanent. The mastoid bone is close to the brain, and occasionally the infection can spread to the brain, causing meningitis or an abscess in or around the brain. How can cholesteatoma be treated? The only treatment we have currently available for cholesteatoma is surgery. The operation is called a mastoidectomy. Occasionally in patients with very small cholesteatoma or in whom surgery may carry significant risks we may opt for a conservative approach, avoiding surgery and simply cleaning the ear out regularly in the out-patients. We would, however, only make this decision after a detailed discussion with the patient, carefully weighing up the risks and benefits of surgery versus a conservative approach.

|