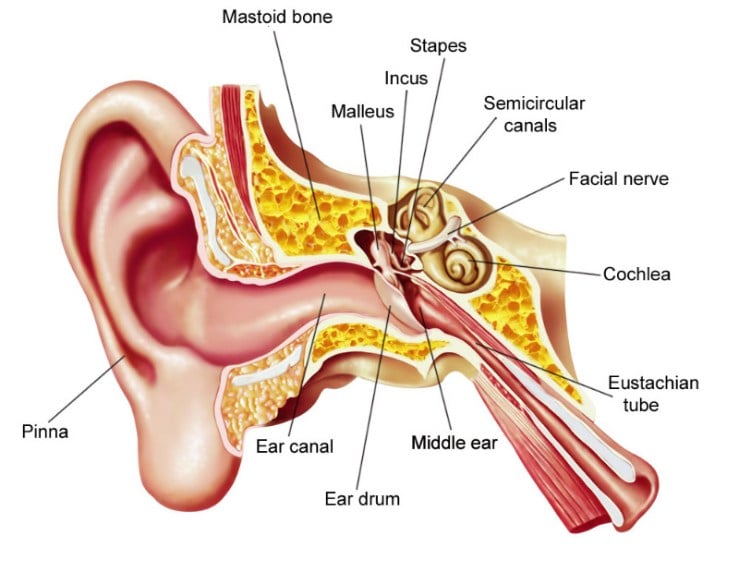

MastoidectomyPLEASE NOTE - THIS INFORMATION IS INTENDED FOR GUIDANCE ONLY. IT IS NOT IN ANY WAY A SUBSTITUTE FOR A SPECIALIST CONSULTATION. Why is mastoidectomy carried out? Mastoidectomy is usually performed to treat a condition called cholesteatoma. This page should be read in conjunction with the page about cholesteatoma. The main aim of the operation is to remove the cholesteatoma and create a dry, safe ear. Patients with cholesteatoma often have an associated hearing loss. With the surgery we aim to make the hearing loss no worse. If there is any thing that can be done to try to improve the hearing at the time of surgery then we will do our best to do this, but it is not always possible, depending on what damage has already occured. Occasionally a limited (cortical) mastoidectomy may be carried out in combination with a myringoplasty, for an ear that is persistently infected but doesn't contain cholesteatoma. This is a different type of procedure from the one described below. Are there any alternatives to surgery? There is currently no way of treating cholesteatoma other than with surgery. In patients with very small cholesteatomas, or if a general anaesthetic would be very risky, we occasionally discuss the option of not operating and managing the ear by cleaning it out regularly in the clinic. In these situations we have to weigh up the risks of surgery against the risks of leaving the cholesteatoma untreated very carefully. Intact canal wall vs. modified radical mastoidectomy You will almost certainly need a CT scan of the bones around the ear prior to surgery. This will help us to judge the extent of the disease, look for any unexpected features and help us when we discuss which is likely to be the best surgical approach for you. The difference between the surgical techniques lies in exactly what bone is removed. This has a significant impact on how the ear is likely to behave in the long term. We will discuss this with you in detail in the out-patients, and often the final decision will be yours. The information here is intended to be used in conjunction with the discussion we will have with you in the clinic. There are a number of different ways of carrying out a mastoidectomy (no two operations are ever exactly the same) but broadly the different techniques fall into two groups. Essentially the choice is either to widen out the whole ear canal, removing the wall of the ear canal and creating what is known as a mastoid cavity (modified radical mastoidectomy), or leave the ear canal intact and work around it (intact canal wall surgery, also known as combined approach tympanoplasty). Modified radical mastoidectomy Cholesteatoma can come back (recur) in two different ways. Firstly if even a microscopic fragment is left behind, it can grow back. Secondly if the reconstructed ear drum collapses again a new cholesteatoma can form. The main benefit of modified radical mastoidectomy is that if the cholesteatoma recurs it should be clearly visible when we examine your ear in the out-patients, because there is nowhere for it to "hide". In the rare cases when it does recur it can generally be dealt with fairly easily, probably under a quick general anaesthetic. The main disadvantage is that the mastoid cavity that is created does need some looking after, and will never be a "normal" ear. You would always need to keep water out of the ear when swimming, showering or bathing, as if any water gets in the ear it would be likely to set off an infection. We normally arrange for you to be fitted with a custom made ear plug for this. The ear would also always tend to collect wax, and mastoid cavities normally need cleaning out in the out-patients every 4-12 months. Intact canal wall surgery This approach is often technically more challenging, as the amount of space in which the surgeon has to work is generally less. Not everyone's ear is suitable for intact canal wall surgery, and the CT scan will give us some of the information we need to assess this. There are a number of other factors we also have to take into account. If your ear is suitable for this sort of surgery it can offer some significant advantages. Leaving the ear canal intact means that it is much more likely that your ear would be waterproof - in other words you would not normally need to wear an ear plug for swimming, showering or bathing. The ear is also much more likely to clean itself of wax. The main disadvantage is that if the cholesteatoma does recur it may not be possible to see it when we examine your ear in the out-patients, and it could then continue to grow unchecked until it causes problems. Because of this, you would need to commit to having a second operation between 9 and 12 months after the first one to check that the cholesteatoma has not come back. This is a similar operation to the first one, with a similar recovery period. If all goes well you should then be left with an ear that needs little or no looking after in the long term (although we would need to monitor you in the clinic for at least 2-3 years). If, however, the cholesteatoma has recurred, we may then be left with the choice of either converting the ear to a mastoid cavity (see above) or possibly committing to one further operation in another 9-12 months. How do I decide between the approaches? We will guide you through this decision-making process. We generally recommend that patients who are fit and active consider should intact canal wall surgery, particularly if they enjoy swimming or other watersports. Patients for whom this is not a concern, and who would prefer to get things sorted out in one operation may prefer to consider modified radical mastoidectomy. From the point of view of hearing, the two approaches have broadly similar results, although intact canal wall surgery may offer more options in terms of reconstruction if the ossicles (bones of hearing) have been extensively damaged by the cholesteatoma.

How is the surgery performed? The operation is carried out under a general anaesthetic (you are completely asleep). It is very delicate, intricate surgery and usually takes between 2 1/2 and 3 hours. All mastoidectomies are carried out via a scar behind the ear. The ear drum is lifted up and some bone is removed from behind and above the ear (the mastoid bone) using a very precise surgical drill and an operating microscope. The cholesteatoma is removed, the ear drum is usually repaired, and if possible the hearing mechanism is reconstructed. The scar is closed with dissolving stitches buried under the skin and a dressing, or "pack" is placed in the ear canal. What can I expect after the surgery? You will probably have a bandage around your head when you wake up. This is to reduce the risk of bleeding or extensive bruising. The bandage will be removed before you go home. If your operation is in the morning you will normally have the bandage removed and be allowed home after 6 hours if you are well enough. If your operation is in the afternoon it is likely you will need to stay overnight. You will be given some pain relief to take home. Because the sutures are dissolving and buried under the skin you will not need to have any sutures removed. The pack in the ear will be removed at your out-patients appointment between 2 and 3 weeks after the operation. While the pack is in place, the hearing in that ear will be reduced. The pack is important because it holds the ear drum back in place and stops the ear canal from narrowing down as a result of scarring. If the pack falls out within the first 10 days after the operation it is important that you get in contact, either via the ward or the appropriate secretary, as it may need replacing. The pack looks like a short piece of crumpled ribbon and may be yellow or brown. You may get small amounts of discharge or bleeding from the ear during the healing process, and this is generally nothing to worry about. However if there is a lot of discharge or if it starts to smell offensive you may have an infection and should either consult your GP or get back in contact directly. Similarly if the wound or external ear start to look red you should seek medical advice. You should plan to take 2 weeks off work following the operation. Children should generally plan to take 2 weeks off school. There is some flexibility in this. If you have a sedentary job or can work from home you may be able to return to work sooner if you wish, but if you have a physically demanding job you may need a little longer. We will, of course, be happy to discuss this with you. You will need to continue to keep water out of your ear for at least 6 weeks following the surgery. You should avoid flying for at least 6 weeks after the operation. During the healing phase, which may last several weeks, you may experience intermittent discharge from the ear. You will generally be given a course of antibiotic ear drops to use for one week after the pack has been removed. It is sometimes necessary to use further courses of antibiotics while the ear is healing. What are the risks of the surgery? All operations, however carefully and expertly they are carried out, have risks attached. As with almost any surgery there is a small risk of infection, bleeding, extensive bruising or a scar that is prominent or heals poorly. The main aim of mastoidectomy is to create a dry, safe ear. There is a chance that we will not achieve this, and that the ear will continue to cause problems with discharge and infection. There is a small chance that further surgery will be necessary. This is in addition to the planned re-look surgery associated with intact canal wall procedures (please see above). We normally tell patients to expect their hearing to be roughly the same after the operation (once the ear has healed) as it was before. However there is a risk that the hearing may get worse, and sometimes we may have to deliberately remove some of the bones of hearing (ossicles) in order to remove the cholesteatoma, causing a reduction in hearing. There is also a chance of complete loss of hearing in the ear, although this chance is extremely small. The hearing in the other ear will, of course, be unaffected. Hearing and balance are closely related, and there is a small chance of the surgery causing dizziness (vertigo) or balance problems. In the rare cases when this does happen it will usually settle down with time. There is a small chance of causing some noises in the ears (tinnitus) or making pre-existing tinnitus worse. If this does happen it will, again, usually settle with time. You may experience some numbness of the top part of the external ear (pinna), which may take a few weeks or months to settle. The nerve that supplies taste to that side of the tongue passes through the ear drum. It is often heavily involved in the cholesteatoma, and it may be necessary to cut or remove a part of this nerve. We know that in most patients with cholesteatoma this particular nerve actually hasn't worked for a while and your taste has adapted over time without you noticing. As a result most people don't notice any effects from having this nerve cut, but you may find you have either a loss of taste down one side of the tongue or a strange, metallic taste. This almost always settles, but may take a few weeks or months to do so. The nerve that moves the muscles on that side of your face also passes through the mastoid bone, very close to where we are operating. We are always extremely careful of this nerve and use special monitoring equipment during the surgery to make sure the nerve isn't being damaged (you may notice some tiny pinpricks in your face from the monitoring equipment after the operation). Nonetheless there is a very small risk of this nerve being damaged. The effects of this could range from a mild weakness of one side of the face that improves on its own in a few weeks to, in the worst case, a complete permanent paralysis of one side of the face. Any sort of facial weakness following mastoidectomy is, however, extremely rare. The ear and mastoid bone are extremely close to the inside of the skull and the brain. Inside the skull is a thick, fibrous layer called the dura, which protects the brain and seals in the fluid that bathes the brain (cerebro-spinal fluid). During the surgery there is a very small risk of the dura being damaged, which would allow the cerebro- spinal fluid to leak out. If this were to happen it would generally be noticed during the operation and the damage repaired. There is, however a tiny chance that the leak would only become apparent after the surgery or that a repair would be unsuccessful. This may then require further surgery to identify and repair the leak.

|